In a recent

Ottawa Citizen article, Kady O' Malley observes...

It seems distinctly unlikely that Joseph Merrill Currier would ever have

predicted that more than a century after his death, he would be

remembered not for his exploits in business or politics, but for the

house he built as a wedding gift for his bride-to-be – and not even the

house itself so much as the address: 24 Sussex Drive...

...There’s not much left of the original Victorian-style villa that Currier

christened Gorffwysfa – Welsh for “place of rest” – and the few

pictures from that era show the house from a distance, making it

difficult to imagine how it must have looked when it was completed in

1868... [emphasis mine, read Ms O'Malley's complete article here.]

Consider O'Malley's remark — "the few pictures from that era show the house from a distance." I don't know what sort of access was to be had during the 19th century, but rest assured that in the 21st, one does not casually stroll onto the grounds of 24 Sussex, with or without a camera. And then there's that irksome scrim of trees all along the front of the property...

There is one striking vantage point available to today's photographers, especially those who own a decent telephoto lens. Consider this shot taken by Wikipedia user "Arsenikk."

Here we see the house atop its limestone bluff, nestled amidst lush greenery, while the Peace Tower and a couple of Canadian flags provide reassuring context. There is only one place i can think of that provides such a view.

This aerial view of Rockcliffe Park indicates the sight-line (in red) across Governor (Governor's, whatever) Bay, from the Ski Hill lookout to 24 Sussex.

The Ski Hill lookout sits at 62 metres above sea level (Ski Hill itself rises to just over 66), while ground level at 24 Sussex is 58 metres. So yes, Arsenikk's photo does look downward, ever so slightly, at its subject. By setting his camera as far west as the terrain would permit (I'm guesing he used a tripod) he was able to capture not only the north side of the house but a reasonable glimpse of the rear facade as well.

* * *

One thing that Ms. O'Malley's article makes clear is that today's 24 Sussex is quite different from the house that Joseph Currier built in the 1800s. The present version may look old, but the building's severe, Romanesque-revival lines actually date to a massive mid-century renovation undertaken in 1950-'51. Currier's original design was smaller and daintier — a Victorian Gothic-revival fairy-castle, bedizened with bay windows and wooden trim, something cozy to charm his new bride.

A bit of chronology will help us understand the house and what happened to it. Let's start with its builder, Joseph Merrill Currier (1820-1884), who was born in Troy, Vermont, and came to Canada at the age of 17. He found work in the lumber trade and established his own mills in Manotick, New Edinburgh and Hull. He was a federal politician both before and after Confederation and was active in businesses including insurance, publishing and railway. Bankrupted by a sawmill fire in 1878, he bounced back to be appointed Ottawa's Postmaster in 1882. He died two years later and was buried at Beechwood Cemetery. Here are some more dates...

1863-1868 — With the help of his brother James, and during his Parliamentary tenure, Joseph Currier designed and built "Gorffwysfa" for his third wife Hannah Wright, granddaughter of Philemon Wright, the founder of Hull.

1884 —Joseph Merrill Currier died on April 22. That same year, the Woodburn Directory (Suburban listings, New Edinburgh) shows "Currier Mrs J M, widow, Ottawa n s" — the address signifying "Ottawa Street, north side."

1893 — On August 4, the first electric streetcar ran on Sussex. There was a return stop directly in front of Gorffwysfa. 1894 — On May 3, the streetcar line was extended into the heart of Rockcliffe Park — the park officially opened that same day. Access to the park would continue to improve through to 1900 when the line was extended to the Dominion Rifle Range at the end of Sandridge (now Manor Park.) In November of that year, the first Rockcliffe streetcar barn was built just downhill from 24 Sussex and Rideau Hall. It (the car barn) tended to catch fire. Repeatedly. The relevance of the streetcars to this discussion will become clear soon enough.

|

| Might Directory, 1901 |

On Janurary 26 1901 Hannah Wright Currier, widow of Joseph Merrill Currier passed away. She she too was buried at Beechwood. Later the same year (or early the next), Gorffwysfa was purchased by the lumber baron and parliamentarian William Cameron Edwards for $30,000. — the 1901 Might Directory lists "Edwards Wm C", not yet moved, still living in Rockland, while the company that bore his name was already well-installed at nearby Rideau Falls.

On March 17 1903, W.C. Edwards was appointed Senator by Sir Wilfred Laurier. Knowing this helps us to date an otherwise undated photo, described as the home of Senator W.C. Edwards.

This is a glass-plate image attributed to William James Topley (1845-1930 "the Man Who Photographed Ottawa"). If nothing else, we can fairly guess that Topley shot this some time between 1903 and 1930 — after which he would have been dead. Knowing this is better than nothing at all.

Topley's early 20th century composition reveals that he faced the same problem that bedevils photographers today — trees. We also know that this picture doesn't quite show Gorffwysfa as Currier designed it because we can see the base of a turret on the left. We are told that Edwards added the turret in 1907 — thus the image dates to 1907 or later.

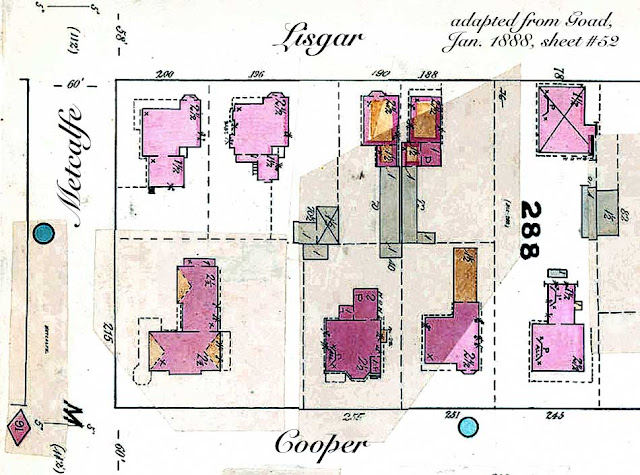

This view of 24 Sussex (then #80 it would seem?) is dated

1912 and gives us an idea of what the property looked like when W.C. Edwards lived there. Note the out-buildings. The "Lodge" to the lower left is now gone. The small stone building next to the main house is actually a shed for the greenhouse that was here, truncated by the edge of the map. (The entire structure appears on Goad's adjacent sheet 3) — the building would ultimately be replaced by the P. E. Trudeau swimming pool. The L-shaped building to the lower right remains to this day, now used as a gatehouse — its wooden deck, extending past the cliff, has been since removed, probably for the better. The wooden

porte-cochère, supported by stone pillars, is said to have been added at the same time as the turret. I don't know who built the back-yard conservatory, but again I suspect Edwards.

1921 — William Cameron Edwards died on September 17. Ownership of Gorffwysfa eventually (circa 1923) passed to his nephew,

Gordon Cameron Edwards, businessman, lumber merchant, and Liberal MP. Gordon Edwards had previously lived at the corner of Charles and Mackay in New Edinburgh.

1943 — from the Ottawa Journal, September 16

"...A claim for $278,697 compensation for the expropriation by the Dominion Government of his Sussex street residence, "Gorphwasfa", has been filed with the Exchequer Court by Gordon C. Edwards. Some months ago the Government filed an offer of $125,000.

The property was first expropriated, according to the Government's explanation, to prevent its being used commercially..."

1945 — from the Ottawa Journal, September 4

"...The former residence of Gordon Edwards, at 24 Sussex street, [was] expropriated this year on [a] ... settlement of $140,000, and reported to be used as the future home of Canadian Prime Ministers or as a guest house for distinguished visitors to Ottawa..."

1946 — On Saturday November 2, Gordon Cameron Edwards died suddenly at his home, 24 Sussex. The house and its four-acre lot effectively passed into the hands of the Canadian Government. In 1947, Australia assumed a brief lease on the address, to serve as that country's High Commission offices. In 1949, Liberal Minister of Trade and Commerce C.D. Howe announced that the property would indeed serve as the Prime Ministers' Residence after some "refurbishment."

Thus endeth our chronology.

The above photo appeared in

Maclean's magazine, which in turn credits it to the

Ottawa Citizen, 1950, though the actual date of the capture is unclear. Note the wistful Red Ensign drooping in front of the

porte-cochère. This is perhaps one of the last, few, clear, close-up views of old Gorffwysfa prior to the great renovation. It's hard not to love all the sticking-out Victorian bits. One can picture Hannah Currier leaning out from the third-storey oreil, waving a handkerchief and shouting "Yoo-hoo!" to lord-of-the-manor Joseph C. as he paces the front yard,

digesting his dinner. But that was then.

|

| an oreil, Nuremburg |

The renovation (at a cost of nearly half a million dollars — figures vary) was completed in 1951. The new design retained much of the house's structural underpinnings, but the interior was fairly gutted and many of the sticking-out bits were lopped off to achieve an austere, Romanesque (bleakly Norman!) appearance. The house's footprint was extended northward by a two-storey side extension (which some people call the "east" side — this being Ottawa.)

It was in this edifice of restrained opulence that Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent took residence. We are told that he was not fully at ease with his sprawling new digs and insisted on paying rent.

|

| almost cozy — even Malak Karsh couldn't get a clear shot |

The rest, as they say, is history. Or rather it was until Stephen Harper moved out in 2015. Some 67 years on, the new, renovated 24 Sussex is old again, sitting empty, cold, and in sore need of extensive and pricey repairs.

* * *

|

| Now is the Winter of our Bleak House, via the National Post |

I'm returning to this POV, as it pertains to three photos from the very early 1900s. Indeed, all the above historical blather has been assembled to provide some perhaps unnecessary context for the charming images which follow.

James Ballantyne (1835-1925) was a businessman (Ballantyne Coal), local politician and champion of education, often described as the Father of Ottawa East. You can read some biographical notes about this "Renaissance man"

here. Ballantyne was an avid naturalist and photographer. Many of his pictures record daily life in and around "Old" Ottawa East, but he also loved to take his friends and family on picnics and nature hikes, camera at the ready.

It was Kady O'Malley's comment about early images, few and from afar, that reminded me of something I first saw a year or two ago.

The Library and Archives Canada (LAC) attributes this photo to the James Ballantyne fonds and describes it as a "Group photograph taken during a picnic 1891." The picture would have been taken either by James himself, or by his daughter Mae.

We may have to quibble about the date, but the location is beyond question. Anyone familiar with Rockcliffe Park will recognise this as the limestone escarpment overlooking Governor's Bay, with Gorffwysfa perched on its promontory in the upper left of the picture. Ballantyne's picnic crew have been posed partway downhill from the (now) Ski Hill lookout, framed by a break in the trees.

(And if I've been harping unfairly about the inconvenience of trees, I should mention that some of the

Eastern White Cedars growing on these cliffs were already mature trees when Samuel de Champlain's canoes first passed below them in the summer of 1613. Respect is due.)

Keep your eye on the woman in the dark dress, standing second from the left. We're about to meet her again.

Here she is, sporting a floppy sun hat. The group has climbed down the escarpment to the beach along the north shore of Governor's Bay. We recognise several people from the previous photo, including the gent with the bowler hat and suspenders, pretending to read his newspaper. I can't quite tell if his gaze is directed at the photographer or toward the young lady in the black hat. The young girl, bottom center, ponders the universe in something round, and someone else has brought an oversized oar that won't be of much use for paddling that canoe.

Look at the building across the bay — the one on top of the cliff...

... 'tis fair Gorffwysfa, seen from afar. If you've noticed that window arrangement of the north facade doesn't match the modern view, that's because the 1950-'51 north extension hasn't been added to the building yet. I'm not 100% about the smaller building to the right, the one with the dormers set in a mansard roof, but I take it to be the roadside "Lodge" on the southeast corner of the property. This is 24 Sussex as it appeared after Joseph Currier had died but while his widow still lived in the house.

Now there's a wee cock-up on the dating of these photos. LAC gives a date of 1891 to the clifftop group shot, but sets the beach scene in 1893. A quibble perhaps, but it a bit of question when we consider our third picture.

Was this an afternoon outing — or a weekend extravaganza?! I count three tents, one pavilion... and a wood stove! Oh, and those oars again. Are they for racing or what? The woman in black is back, seated at the center of the group. And those young ladies are playing lacrosse in the road. The location, to my eye, is halfway down the south-west side of Ski Hill — the curving slope on the left is signature.

I have no doubt that all three images depict the same weekend outing. But in what year? The date bears on the question of how the bloody hell did Ballantyne haul all those people

and all that stuff into the park from his home base at Main Street (just south of the CAR tracks, now the Queensway.)

A wood stove for crying out loud...

The electrified "cars" didn't begin running on Sussex until the first week of August, 1893. So if the picnic took place in that year, the picnickers could have ridden the streetcars as far as 24 Sussex, then descended on foot into the park by the primitive dirt roads that serviced the area back then. I doubt that they would have taken tents with them, let alone a stove. Those items would have been brought in on horse and buggy, presumably loaded and unloaded by the men. If the picnic was held two years earlier, then everything

and everyone was likely brought in by buggy.

Either way, the woods and cliffs past the end of Sussex were still rather rough around the edges. Still recovering from lumbering and sporting two quarries, a sand pit, a marl pit, a clay pit and, somewhere, a lime kiln, the taming of Rockcliffe would properly begin on a Thursday, May 3 1894, when the park officially opened. That weekend, streetcar service began taking day-trippers from the city into the very heart of woods, where a designated meadow clearing provided refreshments, live music, an electric merry-go-round, and a grassy lawn ready to receive everyone's picnic blankets and baskets.

James Ballantyne and his crew were either one or three years ahead of the madding crowd. They cooked their own food and made their own fun, roughing it as they saw fit — whether exploring the cliffs, canoeing, reading newspapers, or girl-watching. And Ballantyne was probably the first photographer to take advantage of a sight-line from Rockcliffe Park to 24 Sussex still used to this day.